The History of Richmond Hill

There is anecdotal evidence that Richmond Hill, the highest hill in Richmond, has been a place of prayer for several millennia. Native Americans have confirmed this use of the hill when the land was still known as Tsenacomoco. The hill overlooks the Falls of the James and faces the setting sun.

There is anecdotal evidence that Richmond Hill, the highest hill in Richmond, has been a place of prayer for several millennia. Native Americans have confirmed this use of the hill when the land was still known as Tsenacomoco. The hill overlooks the Falls of the James and faces the setting sun.

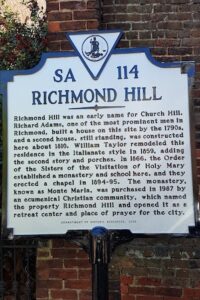

William Byrd II of Westover, granted the land by King James, commissioned Col. William Mayo to lay out a city on Richmond Hill in 1737. The survey lines of Byrd’s and Mayo’s city still form the legal boundaries of the property of Richmond Hill.

Col. Richard Adams, a native of New Kent County, came to Richmond Hill in 1769. At that time, Richmond was still largely undeveloped, a condition which prevailed until it was declared Capital of Virginia in 1779. Adams purchased a number of squares on the southeastern promontory of Church Hill. His initial house was probably located on the north side of Grace Street, across from the present Richmond Hill.

In the mid 1780’s, soon after Richmond became Capital, Adams built an attractive mansion on the crest of Richmond Hill, overlooking the James River and the Shockoe Valley. Adams was Senior Warden of the nearby St. John’s Church, represented Henrico County in the House of Burgesses, and in the House of Delegates and the Senate after Independence, and was one of the 12 founding members of the Common Council of Richmond. He later became its sixth mayor. Writing in his remarkable early history of Richmond, Samuel Mordecai described the prominence of Richard Adams and his descendants in the first half of the 19th Century:

“This hill is divided by little dells into a succession of spurs, forming a cluster of heights overlooking the river, the city and the surrounding country. The proprietor assigned to each of his sons and married daughters one of these prominences. The eldest son, Richard Adams, possessed the fine old family mansion, now Mr. Ellett’s. John erected his mansion east of it, now Mrs. Van Lew’s; William Marshall, who married a Miss Adams, built yet further east, and his house is now the centre of a row, as it was once of an open square, on Franklin, Grace, Twenty-sixth and Twenty-seventh streets.

Southeast of Mr. Marshall, another son-in-law, George W. Smith, placed his residence, a neat wooden building, on Franklin, Main, Twenty-seventh and Twenty-eighth. This gentleman was Governor of Virginia at the time that the Theatre was burned, and was one of the victims, in consequence of his efforts to save others. Samuel G. Adams, the youngest of the sons, erected the building on the western slope of the hill, on Broad Street, now the Bellevue Hospital. The possessions of the Adams family in Richmond and elsewhere gave them a prospect of great wealth in the natural course of things; but impelled by an enterprising spirit, the two younger brothers sought to hasten the event. The chapter on ‘Flush times’ gives the result.

“George Nicolson, once mayor of the city (as was also Dr. John Adams), resided on one of the adjacent and most commanding heights overlooking the city and the surrounding country. The land west of it and south of Mr. Marshall’s and Governor Smith’s, embracing the slope of the hill, has recently been purchased by the city for a public square [now Libby Park]. Mr. Nicolson’s residence was destroyed by fire some years ago. His descendants are among our worthy citizens.”

Tradition holds that the elder Adams failed in his greatest ambition, which was to persuade his friend Thomas Jefferson to place the new State Capitol on the hill which he and his family inhabited. Adams is said never to have spoken with Jefferson following that adverse decision.

In 1859 William Taylor acquired the house which Richard Adams, Jr. had built for $6,500 and by 1860 he had enlarged it significantly, adding a second story, an enclosed cupola, and two-story Italianate porches. In 1860 he sold the house for $20,000 to Richard A. Wilkins, a Virginian who had been running a large sugar plantation in Louisiana, and wished to return to Richmond to educate his children. Wilkins’ young son, Benjamin Harrison Wilkins, often sat in the cupola during the next four years. He watched the smoke and by its movement followed the seven days’ battles when the Yankees attacked Confederate lines north of the city and were forced to move east and south around the city and across the James. Mrs. Wilkins visited the hospitals throughout the city, bringing wounded friends to recuperate in her home. Soon after the war the Wilkins family sold their Richmond Hill mansion to the Catholic Bishop and moved to Tennessee. In the last decade of the century, the embittered son wrote an account of his years, telling of the view from the cupola, entitled War Boy.

In 1866, at the request of Bishop John McGill of the Catholic Diocese of Richmond, the Sisters of the Visitation in Baltimore sent six of their number to establish a monastery and open a girls’ school in the devastated city of Richmond. Following the discipline of their order, they inaugurated daily prayer for the city and the needs of its citizens. Bishop McGill purchased for them the house that Col. Richard Adams had built at the time of the American Revolution, just 80 years before. The Adams mansion had dependencies stretching to the east, and in 1880 the Catholic diocese added to the precinct the Adams-Taylor House, which had been sold to them by the Wilkins family after the war.

The monastery and the girls’ school prospered. In 1894, Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Fortune Ryan, who gave the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart to the Diocese of Richmond, gave a new Chapel to the Sisters of the Visitation. Inscribed across the front wall of the Chapel, in gold leaf, were the first five words of Psalm 83 (AV 84) from the Latin version of the Bible, Quam dilecta tabernacula tua, Domine – “How lovely are thy dwellings, O Lord.” In front were statues of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. The sisters sat in one wing of the Chapel behind a screen, and the students and the public sat in the other.

Soon after 1900, a benefactor gave a new wall to the Sisters, enclosing the growing monastery and school, with their beautiful garden. 22nd Street was donated to the Sisters by the City, and the Sisters gave the steep hillside for Taylor’s Hill Park to the City in return.

In the 1920’s, through the gift of an extraordinary benefactor, the Sisters built a new dormitory building for their boarding school. They demolished the smaller buildings and houses which had linked the Adams mansion and the Adams-Taylor House. And finally, in 1928 or 1929, they demolished the Adams Mansion.

A second major legacy gave the Sisters the opportunity to enlarge the school and monastery once again. Instead, they decided to close the school and use the gift to endow and embrace fully the contemplative life of a monastery. The Sisters moved into the new dormitory building, and established individual cells where the large dormitory rooms had been. From that point on, they fully engaged the contemplative life of prayer and work.

The Sisters of the Visitation produced communion bread for local parishes. Most proudly, in the basement of the Adams-Taylor House they produced the sacramental bread for the Atlantic Fleet during the Second World War. The need for a print shop provoked the demolition of a small porch on the western side of the house, and its replacement with a cinder block wing, designed and erected in 1952 with the help of the Sisters themselves. The present west meeting room of Richmond Hill is on the footprint of the print shop. In 1955, a lightning strike to the nearby Trinity United Methodist Church caused the Sisters to determine to take the cupola off the roof of the old Adams-Taylor House, to prevent such an incident.

The liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council prompted architectural changes within the Monastery. Among these was a significant alteration of the Chapel. The screen separating the Sisters’ Chapel from the main Chapel was replaced with a railing. More dramatically, the altar was brought out from the wall, facing a diagonal axis, the stenciled walls were covered with vinyl, and the 30’ ceiling was lowered in the main Chapel, obscuring the wainscoting and six second story stained glass windows.

Maintenance in the old monastery became more and more of a problem as the Community grew older, as did the many stairs and labyrinthine layout of the buildings. Visitation Sisters came to Richmond with their endowments from several other houses that had closed. After much prayer, the Sisters determined to move to a new site near Rockville in suburban Hanover County, and to build a new monastery. They put Monte Maria up for sale. Nearly every major developer in metropolitan Richmond took a look at the property, but because it had been purpose built, and because it was in an historic district, none was able to make an effective plan.

In February 1986 an ecumenical group, including members of 15 Christian denominations, formed a non-profit corporation to raise money and purchase Richmond Hill. The group, which was based on unprecedentedly broad inter-Christian relationships, was composed of persons who believed that the Lord wanted Monte Maria to stay a place of prayer — feeling that years of capital investment in prayer should not be squandered. Their stated purpose was to preserve Richmond Hill as a place of prayer and to establish a residential Christian community and retreat center there which would pray for the healing of the metropolitan city of Richmond. They saw themselves as stewards of Richmond Hill for the people of the city and for future generations.

They prayed, and sought to raise money. Finally, on November 30, 1987, after a very strange sequence of events, Richmond Hill was able to purchase the monastery. The residential Community began to form in January, 1988. A daily cycle of prayer for Metropolitan Richmond was begun, and initial members made commitments to residency.

After 20 months of difficult negotiations and some minor renovations, the new Community opened Richmond Hill for retreat and classes in the Fall of 1989. Virtually all portions of the monastery were used in ways similar to their use by the Sisters.

By the turn of the century, it had become obvious that the buildings would not survive in useful condition for another decade. In addition, the increased public use and ministry had made clear that there were a number of deficiencies for the purposes for which the monastery was now being used. The Community resolved to engage in a major Capital Program to repair, renovate, and improve the property so that it might survive for another century.

On May 5, 2002, over 200 people came to Richmond Hill to celebrate the start of the long-awaited renovations. The groundbreaking ceremony didn’t actually break ground. No shovels, jackhammers, or wrecking balls were used. Instead, ten founders and community leaders from all over metropolitan Richmond “baptized” the building with water from the Jordan and James rivers. Among those who participated in the blessing were Lieutenant Governor Timothy M. Kaine and Mayor Rudy McCollum.

The crowd then gathered at the end of Grace Street, overlooking the city, as pastors from many of the sponsoring denominations led them in prayer for the metropolitan city.

The renovations were completed in December, 2004, at a total cost of nearly $8 million. In addition to full renovation of the fabric and systems, a cloister and west meeting room were added. The cupola was restored. A lobby, new solarium, elevator, and sundial tower replaced the old solarium and greenhouse. In the former parlors, a theological and spiritual library is divided by the screens which once separated the Sisters from visitors.

Richmond Hill’s residential community consists of 10-15 persons who promise obedience to a common Rule of Life, and sustain a rhythm of prayer three times a day. The focus of intercession is the healing of the community of Metropolitan Richmond. Members of the residential Community commit to residency for a year or more at a time. They receive small stipends. In addition to the in-kind contribution of the residential Community and several hundred volunteers and adjunct staff, the Community is sustained by contributions from groups and individuals. More than 50% of the annual operating budget of the Community comes from charitable contributions of individuals. About 200 different groups, including many churches, non-profit boards, businesses, and government agencies come to Richmond Hill on retreat every year. All are asked to join in the Community’s rhythm of life, breaking for prayer and common meals. Those who do not wish to join in the Chapel are asked to take the prayer time for their own reflection. Richmond Hill sponsors retreats and classes for the public, and offers schools of Spiritual Guidance, Christian Healing Prayer, Vocation, and Race & Justice. Private retreats, spiritual guidance, and healing prayer are available for individuals.